Catalogue Search | MBRL

Search Results Heading

Explore the vast range of titles available.

MBRLSearchResults

-

DisciplineDiscipline

-

Is Peer ReviewedIs Peer Reviewed

-

Reading LevelReading Level

-

Content TypeContent Type

-

YearFrom:-To:

-

More FiltersMore FiltersItem TypeIs Full-Text AvailableSubjectCountry Of PublicationPublisherSourceTarget AudienceDonorLanguagePlace of PublicationContributorsLocation

Done

Filters

Reset

36

result(s) for

"D'Orso, Michael"

Sort by:

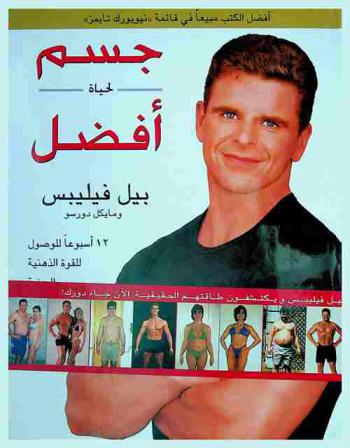

جسم لحياة أفضل : 12 أسبوعا للوصول للقوة الذهنية والبدنية

by

Phillips, Bill مؤلف

,

D'Orso, Michael, مؤلف

,

حسين، كامل يوسف مترجم

in

التمرينات الرياضية

,

اللياقة البدنية

,

القدرة العقلية

2000

يعتبر كتاب \"جسم لحياة أفضل : 12 أسبوعا للوصول للقوة الذهنية والبدنية\" من تأليف بيل فيليبس من أشهر الكتب التي تتحدث عن الرشاقة في العالم، حيث أكد بأن ممارسة الرياضة والمعدة فارغة تسبب إنخفاض مستوى السكر في الدم مما يجعل الجسم يعتمد على حرق الشحوم أكثر من حرق السكريات للحصول على الطاقة.

THE MURDER OF A TOWN NEW YEARS DAY, 1923. AN ALLEGED ATTACK ON A WHITE WOMAN BY A BLACK MAN. FOLLOWED BY A RAMPAGING POSSE HELLBENT ON VENGEANCE. BLOOD IN THE STREETS, BURNING BUILDINGS. AND A ONCE PEACEFUL TOWN DESTROYED BY HATE

1996

It was a three-mile hike down the sand road to the sawmill in Sumner, the sand white as sugar, and most of the men in Rosewood had made the trek that morning. Others had stayed to stoke the flames at the turpentine still just east of the village in a little place called Wylly, and some were even deeper in those dark, wet woods, loggers with hand saws, felling the trees that fed the mill. Among them was James Taylor, 30 years old, soft-spoken, a friendly enough man, with a young wife named Fannie and two small children still asleep in their four-room company-owned home just up the lane from the Cummer and Sons mill. James Taylor's job was to coax the stiff saw blades awake each morning, loosening the steel discs with splashes of oil. Oiling the mill machinery, that's where James Taylor was that morning when the front door to his home burst open and out onto the porch stumbled his wife, sobbing, shrieking, her face battered, her mouth bleeding. Neighbors, mostly women, clambered out onto their porches, some rushing to her side, others sending word up the sawdust-sprinkled drive in the direction of the mill, word that picked up speed as it spread. Something about an attack. By a black man. Over at James Taylor's house. The mob pushed her aside, stormed into the house and found Aaron, up in his mother's bedroom. They dragged him out, ordered him to talk, but he said nothing. So someone called for a rope, and as Emma screamed from the porch, they tied an end around Aaron's wrists and the other to the bumper of a car, a black Model T. The driver hit the gas and Aaron Carrier's body was dragged up the hard dirt road, his shirt torn by the gravel, his skin seared by the sand. A quarter-mile they dragged him, and then they stopped. The driver saying he was tired of wasting his gasoline on this black man. Kill him! someone shouted, and that's when Aaron Carrier spoke.

Newspaper Article

In the Eye of History

1998

Bayard was surprisingly calm. Unlike most of the others, who had thrown in their lot in support of the President's [proposed civil rights] bill and had accepted this march as a show of solidarity with the administration's civil rights proposal, Bayard agreed with most of the things my speech had to say about the bill. He had no problem with the word \"revolution\" or the phrase \"cheap political leaders,\" or even the reference to Sherman. What bothered him right then, and what O'Boyle was apparently most alarmed by, amazingly, was, of all things, the word \"patience.\" Apparently, my calling patience a \"dirty and nasty word\" had sent O'Boyle through the ceiling. Roy Wilkins was having a fit, saying he just didn't understand us SNCC people, that we always wanted to be different. He got up in my face a bit, saying we were \"double-crossing\" the people who had gathered to support this bill. But I didn't back down. I told him I had prepared this speech, and we had a right to say what we wanted to say. \"Mr. Wilkins,\" I told him, \"you don't understand. I'm not just speaking for myself. I'm speaking for my colleagues in SNCC, and for the people in the Delta and in the Black Belt. You haven't been there, Mr. Wilkins. You don't understand.\" I was angry. But when we were done, I was satisfied. So was Forman. The speech still had fire. It still had bite, certainly more teeth than any other speech made that day. It still had an edge, with no talk of \"Negroes\" -- I spoke instead of \"black citizens\" and \"the black masses,\" the only speaker that day to use those terms.

Magazine Article