Catalogue Search | MBRL

Search Results Heading

Explore the vast range of titles available.

MBRLSearchResults

-

DisciplineDiscipline

-

Is Peer ReviewedIs Peer Reviewed

-

Series TitleSeries Title

-

Reading LevelReading Level

-

YearFrom:-To:

-

More FiltersMore FiltersContent TypeItem TypeIs Full-Text AvailableSubjectCountry Of PublicationPublisherSourceTarget AudienceDonorLanguagePlace of PublicationContributorsLocation

Done

Filters

Reset

1,167

result(s) for

"Dunbar, R."

Sort by:

Human evolution : our brains and behavior

\"This book covers the psychological aspects of human evolution with a table of contents ranging from prehistoric times to modern days. Dunbar focuses on an aspect of evolution that has typically been overshadowed by the archaeological record: the biological, neurological, and genetic changes that occurred with each \"transition\" in the evolutionary narrative\"-- Provided by publisher.

Why are there so many explanations for primate brain evolution?

2017

The question as to why primates have evolved unusually large brains has received much attention, with many alternative proposals all supported by evidence. We review the main hypotheses, the assumptions they make and the evidence for and against them. Taking as our starting point the fact that every hypothesis has sound empirical evidence to support it, we argue that the hypotheses are best interpreted in terms of a framework of evolutionary causes (selection factors), consequences (evolutionary windows of opportunity) and constraints (usually physiological limitations requiring resolution if large brains are to evolve). Explanations for brain evolution in birds and mammals generally, and primates in particular, have to be seen against the backdrop of the challenges involved with the evolution of coordinated, cohesive, bonded social groups that require novel social behaviours for their resolution, together with the specialized cognition and neural substrates that underpin this. A crucial, but frequently overlooked, issue is that fact that the evolution of large brains required energetic, physiological and time budget constraints to be overcome. In some cases, this was reflected in the evolution of ‘smart foraging’ and technical intelligence, but in many cases required the evolution of behavioural competences (such as coalition formation) that required novel cognitive skills. These may all have been supported by a domain-general form of cognition that can be used in many different contexts.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Physiological determinants of social behaviour in animals’.

Journal Article

Evolution in the Social Brain

2007

The evolution of unusually large brains in some groups of animals, notably primates, has long been a puzzle. Although early explanations tended to emphasize the brain's role in sensory or technical competence (foraging skills, innovations, and way-finding), the balance of evidence now clearly favors the suggestion that it was the computational demands of living in large, complex societies that selected for large brains. However, recent analyses suggest that it may have been the particular demands of the more intense forms of pairbonding that was the critical factor that triggered this evolutionary development. This may explain why primate sociality seems to be so different from that found in most other birds and mammals: Primate sociality is based on bonded relationships of a kind that are found only in pairbonds in other taxa.

Journal Article

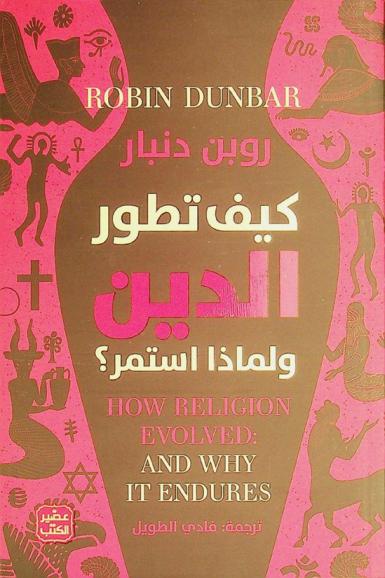

كيف تطور الدين ولماذا استمر ؟

by

Dunbar, R. I. M. (Robin Ian MacDonald), 1947- مؤلف

,

Dunbar, R. I. M. (Robin Ian MacDonald), 1947-. How religion evolved and why it endures

,

الطويل، فادي مترجم

in

الدين فلسفة

,

الديانات فلسفة

2024

في كتابه كيف تطور الدين، يستكشف روبن دنبار هذه الأسئلة وغيرها، مستخلصا الفروق بين الأديان القديمة كما مارستها مجتمعات الصيد في قديم الزمان والأديان العقائدية، من اليهودية والمسحية والإسلام إلى الزرادشتية والهندوسية والبوذية عبر الفحص الذي ينجزه لأصول الدين، والوظائف الاجتماعية وتأثيراته على الدماغ والجسد، ومكانه في العصر الحديث.

New insights into differences in brain organization between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans

by

Pearce, Eiluned

,

Dunbar, R. I. M.

,

Stringer, Chris

in

Animals

,

Biological Evolution

,

Body Mass

2013

Previous research has identified morphological differences between the brains of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans (AMHs). However, studies using endocasts or the cranium itself are limited to investigating external surface features and the overall size and shape of the brain. A complementary approach uses comparative primate data to estimate the size of internal brain areas. Previous attempts to do this have generally assumed that identical total brain volumes imply identical internal organization. Here, we argue that, in the case of Neanderthals and AMHs, differences in the size of the body and visual system imply differences in organization between the same-sized brains of these two taxa. We show that Neanderthals had significantly larger visual systems than contemporary AMHs (indexed by orbital volume) and that when this, along with their greater body mass, is taken into account, Neanderthals have significantly smaller adjusted endocranial capacities than contemporary AMHs. We discuss possible implications of differing brain organization in terms of social cognition, and consider these in the context of differing abilities to cope with fluctuating resources and cultural maintenance.

Journal Article

Thinking big : how the evolution of social life shaped the human mind

When and how did the brains of our hominin ancestors become human minds? When and why did our capacity for language or art, music and dance evolve? It is the contention of this pathbreaking and provocative book that it was the need for early humans to live in ever-larger social groups, and to maintain social relations over ever-greater distances the ability to think big that drove the enlargement of the human brain and the development of the human mind.

Structure and function in human and primate social networks

by

Dunbar, R. I. M.

in

Review

2020

The human social world is orders of magnitude smaller than our highly urbanized world might lead us to suppose. In addition, human social networks have a very distinct fractal structure similar to that observed in other primates. In part, this reflects a cognitive constraint, and in part a time constraint, on the capacity for interaction. Structured networks of this kind have a significant effect on the rates of transmission of both disease and information. Because the cognitive mechanism underpinning network structure is based on trust, internal and external threats that undermine trust or constrain interaction inevitably result in the fragmentation and restructuring of networks. In contexts where network sizes are smaller, this is likely to have significant impacts on psychological and physical health risks.

Journal Article

Thinking big : how the evolution of social life shaped the human mind

When and how did the brains of our hominin ancestors become human minds? When and why did our capacity for language or art, music and dance evolve? It is the contention of this pathbreaking and provocative book that it was the need for early humans to live in ever-larger social groups, and to maintain social relations over ever-greater distances the ability to think big that drove the enlargement of the human brain and the development of the human mind. This social brain hypothesis, put forward by evolutionary psychologists such as Robin Dunbar, one of the authors of this book, can be tested against archaeological and fossil evidence, as archaeologists Clive Gamble and John Gowlett show in the second part of Thinking Big. Along the way, the three authors touch on subjects as diverse and diverting as the switch from finger-tip grooming to vocal grooming or the crucial importance of making fire for the lengthening of the social day. Ultimately, the social worlds we inhabit today can be traced back to our Stone Age ancestors.

Breaking Bread: the Functions of Social Eating

2017

Communal eating, whether in feasts or everyday meals with family or friends, is a human universal, yet it has attracted surprisingly little evolutionary attention. I use data from a UK national stratified survey to test the hypothesis that eating with others provides both social and individual benefits. I show that those who eat socially more often feel happier and are more satisfied with life, are more trusting of others, are more engaged with their local communities, and have more friends they can depend on for support. Evening meals that result in respondents feeling closer to those with whom they eat involve more people, more laughter and reminiscing, as well as alcohol. A path analysis suggests that the causal direction runs from eating together to bondedness rather than the other way around. I suggest that social eating may have evolved as a mechanism for facilitating social bonding.

Journal Article