Catalogue Search | MBRL

Search Results Heading

Explore the vast range of titles available.

MBRLSearchResults

-

DisciplineDiscipline

-

Is Peer ReviewedIs Peer Reviewed

-

Series TitleSeries Title

-

Reading LevelReading Level

-

YearFrom:-To:

-

More FiltersMore FiltersContent TypeItem TypeIs Full-Text AvailableSubjectCountry Of PublicationPublisherSourceTarget AudienceDonorLanguagePlace of PublicationContributorsLocation

Done

Filters

Reset

614

result(s) for

"Eco, Umberto"

Sort by:

Confessions of a young novelist

Umberto Eco, author of \"The Name of the Rose,\" looks back on his long career as a theorist and his more recent work as a novelist, and explores their fruitful conjunction.

Where are you?

2014,2020

This book sheds light on the most philosophically interesting of contemporary objects: the cell phone. \"Where are you?\"--a question asked over cell phones myriad times each day--is arguably the most philosophical question of our age, given the transformation of presence the cell phone has wrought in contemporary social life and public space. Throughout all public spaces, cell phones are now a ubiquitous prosthesis of what Descartes and Hegel once considered the absolute tool: the hand. Their power comes in part from their ability to move about with us--they are like a computer, but we can carry them with us at all times--in part from what they attach to us (and how), as all that computational and connective power becomes both handy and hand-sized. Quite surprisingly, despite their name, one might argue, as Ferraris does, that cell phones are not really all that good for sound and speaking. Instead, the main philosophical point of this book is that mobile phones have come into their own as writing machines--they function best for text messages, e-mail, and archives of all kinds. Their philosophical urgency lies in the manner in which they carry us from the effects of voice over into reliance upon the written traces that are, Ferraris argues, the basic stuff of human culture. Ontology is the study of what there is, and what there is in our age is a huge network of documents, papers, and texts of all kinds. Social reality is not constructed by collective intentionality; rather, it is made up of inscribed acts. As Derrida already prophesized, our world revolves around writing. Cell phones have attached writing to our fingers and dragged it into public spaces in a new way. This is why, with their power to obliterate or morph presence and replace voice with writing, the cell phone is such a philosophically interesting object.

Confessions of a Young Novelist

2011

Umberto Eco published his first novel, The Name of the Rose, in 1980, when he was nearly fifty. In these \"confessions,\" the author, now in his late seventies, looks back on his long career as a theorist and his more recent work as a novelist, and explores their fruitful conjunction.

He begins by exploring the boundary between fiction and nonfiction—playfully, seriously, brilliantly roaming across this frontier. Good nonfiction, he believes, is crafted like a whodunnit, and a skilled novelist builds precisely detailed worlds through observation and research. Taking us on a tour of his own creative method, Eco recalls how he designed his fictional realms. He began with specific images, made choices of period, location, and voice, composed stories that would appeal to both sophisticated and popular readers. The blending of the real and the fictive extends to the inhabitants of such invented worlds. Why are we moved to tears by a character's plight? In what sense do Anna Karenina, Gregor Samsa, and Leopold Bloom \"exist\"?

At once a medievalist, philosopher, and scholar of modern literature, Eco astonishes above all when he considers the pleasures of enumeration. He shows that the humble list, the potentially endless series, enables us to glimpse the infinite and approach the ineffable. This \"young novelist\" is a master who has wise things to impart about the art of fiction and the power of words.

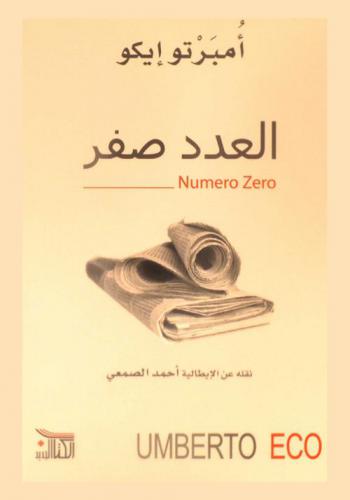

العدد صفر : رواية

2017

في هذه الرواية الجديدة لإيكوهو تشابك الحاضر بالماضي، فإذا بالكتاب يسرد لنا تاريخ إيطاليا في العقود الأخيرة من القرن المنصرم، ملونا إياها يشبح موسوليني زائف يعود لتسلم السلطة مرة أخرى ولكنه يموت فجأة ويخفق الانقلاب على الدولة. مؤامرة ربما تكون قد نشأت في مخيلة (برغادوتشيو) المحرر الذي هو أكثر هوسا من غيره بفكرة المؤامرة الكونية التي تشترك فيها أطراف سياسية والفاتيكان والاستخبارات المركزية الأمريكية والماسونية وبعض الأوساط المالية وكان ظن الجميع أن كل ذلك من مبتكرات عقل (برغادوتشيو) المريض ولكن عندما عثر عليه مقتولا صار كل شيء حقيقة. رواية إيكو متاهة جديدة مخيفة أكثر من سابقاتها لأنها تجعلنا نتساءل : هل نحن أيضا، في كل يوم، ضحية أيد تعمل في الخفاء من خلال الصحف وقنوات التلفاز وتحركنا مثل الدمى وإذا برغبتنا في معرفة الحقيقة تتحول إلى خوف من اكتشاف الحقيقة.

How to Write a Thesis

2015

By the time Umberto Eco published his best-selling novelThe Name of the Rose, he was one of Italy's most celebrated intellectuals, a distinguished academic and the author of influential works on semiotics. Some years before that, in 1977, Eco published a little book for his students,How to Write a Thesis, in which he offered useful advice on all the steps involved in researching and writing a thesis -- from choosing a topic to organizing a work schedule to writing the final draft. Now in its twenty-third edition in Italy and translated into seventeen languages,How to Write a Thesishas become a classic. Remarkably, this is its first, long overdue publication in English. Eco's approach is anything but dry and academic. He not only offers practical advice but also considers larger questions about the value of the thesis-writing exercise.How to Write a Thesisis unlike any other writing manual. It reads like a novel. It is opinionated. It is frequently irreverent, sometimes polemical, and often hilarious. Eco advises students how to avoid \"thesis neurosis\" and he answers the important question \"Must You Read Books?\" He reminds students \"You are not Proust\" and \"Write everything that comes into your head, but only in the first draft.\" Of course, there was no Internet in 1977, but Eco's index card research system offers important lessons about critical thinking and information curating for students of today who may be burdened by Big Data.How to Write a Thesisbelongs on the bookshelves of students, teachers, writers, and Eco fans everywhere. Already a classic, it would fit nicely between two other classics:Strunk and WhiteandThe Name of the Rose.This MIT Press edition will be available in three different cover colors.ContentsThe Definition and Purpose of a ThesisChoosing the TopicConducting ResearchThe Work Plan and the Index CardsWriting the ThesisThe Final Draft

Chronicles of a liquid society

Posthumously collects short essays from the author that reflect on the changing modern world, touching on such topics as popular culture, politics, being seen, conspiracies, the old and the young, new technologies, mass media, racism, and good manners.

From the tree to the labyrinth : historical studies on the sign and interpretation

by

Eco, Umberto

,

Oldcorn, Anthony

in

Language and languages

,

Language and languages -- Philosophy -- History

,

LITERARY COLLECTIONS / Essays

2014

How we create and organize knowledge is the theme of this major achievement by Umberto Eco. Demonstrating once again his inimitable ability to bridge ancient, medieval, and modern modes of thought, he offers here a brilliant illustration of his longstanding argument that problems of interpretation can be solved only in historical context.

A la espera de una semiotica de los tesoros

2015

Reflexión llena de humor sobre la profusión y curiosa riqueza de los tesoros almacenados en los palacios y catedrales de la antigüedad.

Journal Article