Catalogue Search | MBRL

Search Results Heading

Explore the vast range of titles available.

MBRLSearchResults

-

DisciplineDiscipline

-

Is Peer ReviewedIs Peer Reviewed

-

Reading LevelReading Level

-

Content TypeContent Type

-

YearFrom:-To:

-

More FiltersMore FiltersItem TypeIs Full-Text AvailableSubjectCountry Of PublicationPublisherSourceTarget AudienceDonorLanguagePlace of PublicationContributorsLocation

Done

Filters

Reset

10

result(s) for

"Robinson, Marilynne. Housekeeping"

Sort by:

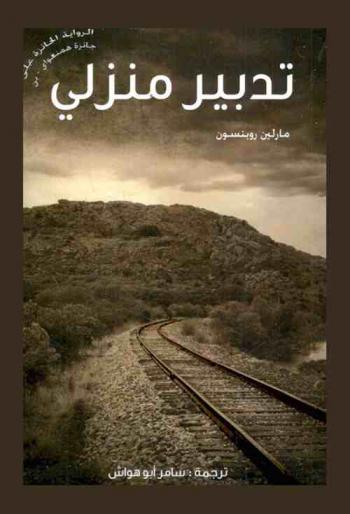

تدبير منزلي

by

Robinson, Marilynne مؤلف

,

Robinson, Marilynne. Housekeeping

,

أبو هواش، سامر، 1972- مترجم

in

القصص الأمريكية قرن 21 ترجمات إلى العربية

,

الأدب الأمريكي قرن 21 ترجمات إلى العربية

2011

تلمسك هذه الرواية بعمق من خلال بلاغتها الجميلة جدا، والتى تود أن تقرأها مرارا وتكرارا فقط لكي تتذوق الكلمات، الرواية تتحدث إلى القلب والروح عن الدولة الانتقالية ولتكن حياتنا مثلا في حين تلمس توقعاتنا وتجاربنا في هذه الحياة .. الرواية ليست مجرد قصة عابرة أو مؤقتة ولكنها أكبر من ذلك بكثير، تحكي الرواية قصة شقيقتين روث ولوسيل ؛ من هم وكيف سيصبحون هذا ما سنتعرف عليه داخل هذه الرواية الممتعة.

A COLONY OF THE DISGRUNTLED

by

Marilynne Robinson is the author of "Housekeeping," a novel

,

Robinson, Marilynne

in

O'BRIEN, EDNA

,

ROBINSON, MARILYNNE

1988

To [Anna], Moorish Catalina suggests abandon and release. But she, it turns out, is modern, too, with a broken marriage, a dismal affair and a child whose paternity has been established by blood tests. She has read enough to have discovered an earth goddess, Gaia, and with her perhaps a willingness to be seduced by Anna, to be ''eclipsed inside the womb of the world.'' It is characteristic of urban Western culture to consider its newest tolerance a recovery of the primordial, appropriately acted out among the earthy folk at the cultural margins. But their tryst causes outrage in her village, as Anna had reason to expect it would. The lavish respect accorded to the pretty gravity of peasant life vanishes when it is found to be severe at its heart. The Irish [Van Gogh] defaces village walls with the word ''lesbos,'' in retaliation for its being painted on Catalina's family house. So much for unspoiled beauty. Disaster comes of Anna's inability to let things be. While she rummages through experience for a salve to cure her own hurt soul, she never thinks what injuries she might inflict. The fetish, or trophy she carries away at the end is Catalina's bloody hair, ''so vibrant, so alive it was as if her face still adhered to it.'' Her gloss on the text ''resurrexi'' would seem to be that her own angst is ended by the death of a young, generous, interesting woman. The concept of rebirth is as diminished as the concepts of art and of self-discovery.

Book Review

Marriage and Other Astonishing Bonds

by

Marilynne Robinson is the author of "Housekeeping," a novel

,

Robinson, Marilynne

in

CARVER, RAYMOND

,

ROBINSON, MARILYNNE

1988

For 150 years or so, every kind of art whose style has caused it to be identified as ''modern'' has been interpreted in the same way - as a contemplation of, and protest against, a world leached of pleasure, voided of meaning, spiritually and culturally bankrupt, etc. This is supposedly the ''modern condition,'' which we are schooled to accept as an objectively existing thing, like the Rock of Gibraltar. No matter that, by every measure, this teeming nation is, as it always has been, rapt as Byzantium, its man in the street entirely accustomed to viewing his life in cosmic terms. Such structuring and valuing habits of mind, we tell ourselves, are just what our age and culture lack, a deficiency our arts boldly mirror, being more or less helpless to do otherwise. The idea of ''the modern'' is now so very old it has had to be repackaged as ''the post-modern'' and covered with assurances that the new product is starker, more cynical, altogether more abysmal than the one we are accustomed to. In ''Bicycles, Muscles, Cigarettes,'' a man comes to the defense of his young son, who is in trouble with neighbors. The boy expresses his affection for his father by telling him that he hopes not to forget his grandfather, and he wishes he could have known his grandfather at his father's age, and his father at his own age, yearning to imagine himself into their lives, simply to intensify his pleasure in his own. In ''Distance,'' a divorced man tells his grown daughter, whom he sees only on rare occasions, a story about her infancy, calling himself and her mother ''the boy'' and ''the girl.'' At the end of the story they both regret the loss of the galled, warm, commonplace life they have conjured. ''Menudo'' is about a man caught miserably in an infidelity, on the point of losing his second wife when he has not really recovered from the loss of his first. ''Elephant'' is a wonderful little story that should put paid, if anything ever will, to a clamor in certain quarters for a [Raymond Carver] story about grace and transcendence. The narrator, a sort of suburban Pere Goriot, is being bled of his substance by a former wife, a mother who is ''poor and greedy,'' a shiftless son, a shiftless daughter with two children and a live-in good-for-nothing, and a brother who calls with hard-luck stories. The man is impoverished, exhausting his credit, working and worrying, trying to meet their endless demands. Then he dreams that his father is carrying him, as a child, on his shoulders. The image brings him a great release. He thinks of his daughter, ''God love her and keep her,'' and hopes for the happiness of his son, and is glad that he still has his mother, and that his former wife, ''the woman I used to love so much,'' is alive somewhere. Then perhaps he dies. He is carried past the place where he works at astonishing speed in a ''big unpaid-for car.'' Whether it is death that has stopped for him, or an uncanny freedom, the exhilaration of the ending has a distinctly theological feel.

Book Review

THE FAMILY GAME WAS REVENGE

by

Marilynne Robinson is the author of "Housekeeping," a novel

,

Robinson, Marilynne

in

ROBINSON, MARILYNNE

,

TAYLOR, PETER

1986

They are seldom distinguished for good or evil. Their ''manners'' are the terms in which their lives are understood, terms that, in Mr. Taylor's world, differ bewilderingly even as between Memphis and Nashville. In his beautifully ironic new novel, ''A Summons to Memphis'' - his only previous novel, ''A Woman of Means,'' appeared 36 years ago - he describes, with scarcely a smile, how a family is destroyed by a betrayal, rarely mentioned even among themselves, that took place more than 40 years before. Phillip Carver, the 49-year-old son of the family, is called back to Memphis by his two older sisters to prevent their widowed father from remarrying. In narrating the story of his return, he recalls how the treachery of their father's business partner caused the family to remove from Nashville and a life blessed with meaning to Memphis and gathering despair. The change is only the more insidious for being almost undetectable. The father, in making his dignified retreat from Nashville, the scene of his betrayal, shocks his family profoundly. His wife takes to her bed and his children remain unmarried, the two daughters still dressing like girls in corpulent middle age, a sort of taunting allusion to the time when the rituals that would have supported their passage through life were disrupted. The shock of their father's being betrayed is transmitted as his betrayal of them. The narrator, too, who has long since moved to Manhattan and established a life there with a Jewish woman from Cleveland, attempting to naturalize himself to the part of the world that is not Tennessee, blames his father for disrupting his only chance at marriage, when he was a young man. So the family is frozen in one moment, the offspring oxymoronically ''middle-aged children'' far too engrossed with their father. A recoil is built into the situation. The children do as they feel they have been done by. They betray. IN ''A Summons to Memphis,'' as in tragedy - I take the title to invite such comparisons -what these people do for reasons that are personal and unique to them, and wholly sufficient to account for their actions, coincides neatly with larger patterns that exist outside them. Oedipus went to Thebes imagining himself a stranger. These people have considered themselves strangers in Memphis. Yet, as the narrator makes clear from the beginning, anticipating events as precisely as any oracle, they re-enact a situation he sees as ''some kind of symbol . . . of Memphis'' - in the typical pattern he observes in that city, ''a rich old widower'' is ''denounced and persecuted by his own middle-aged children'' when he decides to remarry. While the energy of malice in the Carver children comes from their being obliged to move to this alien place, its last expression takes a form that makes it clear they are assimilated to Memphis altogether. It seems natural for [Peter Taylor], so attuned to family mysteries, to say of meeting Gertrude Stein, ''She was like an old aunt, chatting.'' In ''A Summons to Memphis'' the narrator introduces himself to Stein on a Paris street while stationed there during World War II; soon they're gossiping about Memphis acquaintances. That happened to Mr. Taylor, but part of the story didn't suit his book. ''I meant to say, 'Miss Stein, I'm a young American writer,' but I got excited and said, 'Miss Stein, I'm a young American soldier.' I was wearing my uniform and she looked at me and said, 'I see that you are.' ''

Book Review

WRITERS AND THE NOSTALGIC FALLACY

by

Marilynne Robinson is the author of "Housekeeping," a novel. She is writing a nonfiction book on contemporary British society and culture

,

Robinson, Marilynne

in

Doctorow, E L (1931-2015)

,

Dunn, Robert

,

Stowe, Harriet Beecher

1985

This artifice, this past, while it is beautiful and legitimate, is not the past. It is a gross error to mistake it for history. History is slow, slovenly, bloody, disheveled - our authentic ancestor, in whose lineaments we can clearly discover all our vices, the disreputable parent who cursed us once in our birth and twice in our rearing. We hardly need to cultivate a sense of history. We bar our doors and windows against the consequences of its blood feuds, bad debts, schemes to get rich quick, its crack-pate enthusiasm. It ate the sour grapes that have set our teeth on edge. Its chickens come home to roost in our living rooms. We are all too intimate with history; our lives are joined to it without a seam. B UT the idea of a breach, a before and an after with some Catastrophe in between to account for a grand-scale qualitative decline, and the application to experience of this paradigmatic mythic structure, is taken very generally to constitute a sense of history. Of course the past is always put to polemical use. Favored values are always ''traditional,'' privileges are always ''ancient.'' Still, the error of treating the artificial, value-shaped past as an authentic, historical past - which is as fundamentally naive as supposing our dwarfed and poxy forebears looked like paintings and statuary -seems to me to have entered our tradition with the literature of European reaction, early in the 19th century. Take courtly and ecclesiastical culture as culture indeed, and modern, mass and democratic influences as anti-culture, create explicit or implicit contrasts - and you have a modernist poem. ''The Waste Land'' epitomizes this method, exposing the vulgarity of the lower-class lovers in the boat on the Thames by invoking Shakespeare's Enobarbus's North's Plutarch's Cleopatra on her barge. Shakespeare looked out on a reechier Thames than ever Eliot did - his theater was downwind of a river so foul that the authorities left the actors and bearbaiters who did business there largely unmolested. The vision of beauty Shakespeare conjures when he describes Cleopatra comes straight from a book, and one more remote from his experience by far than his was from Eliot's. He could as well have pointed the same sort of contrast Eliot did, if he had been less sophisticated. But that very play, ''Antony and Cleopatra,'' is about history as myth and artifice. Shakespeare, unlike Eliot, took into account the nature of the material he was dealing with. Where, but in custom and in ceremony, are innocence and beauty born? Well, just about anywhere, actually. But to cherish the opinion that innocence and beauty can flourish only in certain social conditions is to make alternative conditions ''cultureless,'' devoid of the sweetest graces of human life. All sorts of European writers have appalled themselves at the thought, and sometimes the spectacle, of our ''culturelessness'' - an affliction by which we have never been especially plagued. Emerson and Whitman, among others, solved the problem of developing a democratic esthetic by finding the origins of poetry in the workings of consciousness, perception and language. An elegant solution. Still, the old notion of culture has worked powerfully with us, too. It has clouded the wonderful transparency and openness of Melville and Whitman. Now we assume a posture of judgment and censure toward our fel-lows, as our best writers never did. We make images of banality out of banal language, though to do so, if appropriate to our cultural circumstance, is then redundant, like robbing the poor, and unprofitable, like beating the mad. This approach must be based on the notion that writers in other times simply fell into resonance and felicity as part of their historical lot, the way we have fallen into wonder drugs and household appliances. We are indignant that life is not art. For the same reasons, I cannot be a writer of ''political'' fiction. Everything, of course, is political, in the sense I take from Aristotle, that political order is the shape of a distinctive life. But ''political'' is a much more restrictive category. To qualify, one must observe elaborate conventions about how history and human nature are to be described. These conventions look to me to be as inadequate to body out a world as the stock figures of melodrama or as Plautus's stock figures, Senex and Meretrix, in their Roman street. If decency requires us to take these conventions seriously, that is a great sign in itself that things have gone wrong.

Newspaper Article

A LONG AND WRETCHED VIGIL

by

Marilynne Robinson is the author of "Housekeeping," a novel. She is writing a nonfiction book on contemporary British society and culture

,

Robinson, Marilynne

in

Blackwood, Caroline (1931-1996)

,

Robinson, Marilynne

1985

Nor does Miss Blackwood, who is a novelist and the widow of Robert Lowell, tell us much about Greenham Common itself. Who are these women? ''Women often hardly knew each other's names on the camps. . . . They were just 'women' and they shared a terror of 'nukes' and that was all they had to unify them.'' Miss Blackwood makes the acquaintance of a nurse named Pat. When, later, she inquires after her, someone asks, ''Do you mean older Pat?'' She muses, ''I imagined that I did, but they probably had many Pats on the base.'' There were as well a ''mongol'' (a person with Down's syndrome) and a girl who seemed mentally ill, punks with shaved heads and lesbians who, in Miss [Caroline Blackwood]'s happy phrase, ''seemed determined to overegg the sexual pudding.'' They kissed in public. Then at the top of the next page, we find the English writer Auberon Waugh credited with the claim that ''the Greenham women smelt of 'fish paste and bad oysters,' '' which remark, Miss Blackwood says, ''also haunted me for it had such distressing sexual associations.'' I must take her word for that. As to the health of political dialogue in which it is considered telling and appropriate to speak of one's adversaries in such terms, I have my own views. Miss Blackwood takes the stance of one entirely prepared to believe these reports. On approaching a gray-haired woman, she says: ''If she was a Greenham witch, I hated the idea that she might get up and scream at me. If she was as destructive as I'd been told, she might give me a vicious stab with her knitting needles. But above all, I dreaded that she might suddenly behave like a dog and defecate.'' The real preoccupations of ''On the Perimeter'' are violence, sexuality and filth in various forms. In telling the story of ''peace women'' camped near a country town, Miss Blackwood has continual recourse to words like ''loathing,'' ''hatred,'' ''terror,'' ''repulsion.'' The two British paratroopers who watch her arrive are ''like ferocious animals as they glared at the benders with an expression of venomous hatred.'' Their ''nasty yellow-eyed expression'' makes her speculate that ''they saw the peace campers as leprous and felt that anyone who had any contact with them might spread the contagion throughout the community, and for this reason would be better exterminated.'' Nor are these yellow-eyed soldiers the worst of their troubles. ''The hooligan youths from Newbury came down in the night and poured pigs' blood and maggots and excrement all over them'' -enough, surely, to dispel the odor of sanctity. Of the soldiers' ''bellowing their horrible obscenities,'' she says, ''They seemed besplattered with their own oaths and soiled by their own sordid fantasies.'' She reports that ''the brutal youths from Newbury . . . drove past the camps screaming maniacal abuse at the women,'' who, for their part, ''loathed and feared'' weapons and force as ''manifestations of masculinity.''

Book Review

GROWING UP THANKLESS

by

Marilynne Robinson, the author of the novel ''Housekeeping,'' is working on a nonfiction book about contemporary

,

Britain., MARILYNNE ROBINSON

in

DRABBLE, MARGARET

,

ROBINSON, MARILYNNE

1987

Things are not simple, however. There are ligatures of blood and mere coincidence that bind these worlds together. Liz Headleand, whose story is the center of this diffuse narrative, has a problem of identity. A classic [Margaret Drabble] heroine, she endured her childhood in a crabbed, spent Northern town called Northam. Since Cambridge her successes have included a distinguished marriage and inclusion in a marginal but authentic part of the British nomenklatura. The narrative worries at the problem of legitimacy of her claim to the status she has achieved. She is, after all, a product of the now-discredited postwar idealism. In ''the brave new world of Welfare State and County Scholarships,'' she and her friends were ''the elite, the chosen, the garlanded of the great social dream.'' ''The Radiant Way'' begins with a 1979 New Year's Eve party at Liz's house, a slightly ambivalent celebration of the new post-idealist era. It is a time of winnowing. The language of Darwin and Herbert Spencer is of use. In the course of the novel, characters of foreign extraction leave the country, a working-class professor finds himself returned to the north and toil at the educational coalface with the disadvantaged and illiterate. Brahmins fall back on old resources, finding what comfort they can in wealth and advantage. All this stirs memories of inappropriate behavior by him toward them (associated for [Liz], oddly enough, with the child's book ''The Radiant Way,'' which was also the title of an early, idealistic documentary made by her husband to stimulate educational reform). To illustrate the fact that things could have been worse for them, Liz ''regaled Shirley with one or two worse cases that had come her own way. Stunned children, reeling from confrontation with bull-headed minotaurs.'' A pretty moment, truly. It is no surprise by now that these weird sisters have not a word of compassion for their mother's unenviable life, even when they learn the secret of it. The point is made that Liz is right to deny these compromising parents, even to refuse them all sympathy. She is herself alone. And the reader is left to wonder what this creature is that is being held up to our admiration.

Book Review

THE GUILT SHE LEFT BEHIND

by

Marilynne Robinson is the author of the novel "Housekeeping."

,

Robinson, Marilynne

in

Courtney, Iris

,

Oates, Joyce Carol (1938- )

,

Robinson, Marilynne

1990

''Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart,'' like Ms. [Joyce Carol Oates]'s recent novels ''You Must Remember This'' and ''Marya,'' has as its heroine a bright young woman (this one named Iris) who, in the course of the narrative, rises like a mote of light out of the tenebrous urban nether world to take her place among the cultured and secure and be recognized by them as one of their own. In the opening scenes of the novel, the body of a teen-age boy called Little Red Garlock is pulled from a river. The two main characters, Iris Courtney and Jinx Fairchild, share responsibility for the killing. They are in high school when it happens, both good students: Iris a girl compensating for a tawdry and disrupted home life with a passionate bookishness, and Jinx a basketball player enjoying local adulation and what seems the certainty of a college scholarship. In the novel's time and place, the late 1950's and early 1960's in upstate New York, there is no great likelihood that the authorities or the public will react temperately to what they have done or take extenuating circumstances into account - because Jinx Fairchild is black. The opening scene, the discovery of the body, is presented through the eyes of an unnamed fisherman who sees gulls with ''dangling pink legs like something incompletely hatched'' and to whom the river mist seems as ''clammy as the interior of another's mouth.'' The precision of this language is of a kind with the uncanny aptness of dream imagery, communicating its brilliant flood of sensory and emotional experience, which always beggars language. At the end of this scene, after the police and the curious onlookers have gone, the voice describes the waves' ''slap, slap, slap . . . like the pulse of a dream that belongs to no one, no consciousness, thus can never yield its secrets.'' Ms. Oates's book is full of such declarations of its method. ''No visual truth, only inventions. No 'eye of the camera,' only human eyes.'' Iris, whose mother chose her name to suggest not a flower but an eye, has learned this ''one clear truth'' from her uncle, a photographer who is as greedy to capture human images as Ms. Oates is herself, and is driven by the same compulsion to prove that there is not only an esthetic but also at least the suggestion of an order to be discovered in their sheer accumulation.

Book Review

AT PLAY IN THE BACKYARD OF THE PSYCHE

by

By Marilynne Robinson

,

Marilynne Robinson is the author of the novel "Housekeeping."

in

ROBINSON, MARILYNNE

,

UPDIKE, JOHN

1987

Some of these stories seem to me less than wonderful. They involve New England social-climbing, and the affairs of edgy and unrealized women. Mr. [John Updike]'s interest in the former is Godlike - not, in this context, a synonym for creditable. In terms of divine attention, surely any sparrow fighting a down draft enjoys priority over the dance of social spheres in the elderly towns of Massachusetts. If these spheres must be tended to it can only be on the grounds that everything must finally be tended to, not because, in themselves, they compel attention. The conflict in ''More Stately Mansions'' between a Yankee descended from mill owners and an Italian descended from mill workers is a patient recounting of two minor strains of bad behavior. In this story and in ''A Constellation of Events'' and ''The Other,'' intimate relations are entered into with or by women who are characterized by nothing so much as the perplexed and fascinated distance from which the author views them. These women have an auntish tendency to deflect the imagination from any thought that passion could actually touch them. Having said this, I may now praise with added emphasis the stories that are wonderful, indeed, beginning with ''The City,'' a sort of inversion of Tolstoy's ''Death of Ivan Ilych.'' In Tolstoy's work, the protagonist dies in the bosom of his family, which is irked and indifferent and refuses to attach importance to the seriousness of his illness, and to the ultimate seriousness of death itself. In ''The City,'' a traveling computer salesman learns from a novel discomfort in his bowels the lonely fact that things are not as they should be. He grows worse in a hotel room, and entrusts himself finally to the care of a municipal hospital. THE city of the title, which remains nameless, could be any one of scores of cities in the American interior. It has a calm, distinctive, rural accent, an unselfconscious diversity of population, a renewed center, a few skyscrapers, an art museum containing one or two indubitable treasures. Here Carson, the main character, falls into the net of generalized, grand-scale solicitude. He is rescued and healed by strangers, among strangers. Convention would have this a cold and anomic experience, but in this story it is beautiful. Book'' and ''[Henry Bech] Is Back,'' Mr. Updike has written 12 novels, plus five volumes of poetry and three collections of criticism. That versatility reflects his literary skills and interests, but it also reflects fealty to a promise the author made early in his career. ''I vowed that every other book would be a novel, but in between they would be stories or poetry or criticism or essays,'' he explained. ''My figuring was, the novels might make money and the others might lose it, so for every downer I owe my publisher an upper.''

Book Review

WORKING TO MAKE LIFE PRETTIER

by

Marilynne Robinson is the author of the novel "Housekeeping."

,

Robinson, Marilynne

in

Lauterstein, Ingeborg

,

Meinert, Reyna

,

ROBINSON, MARILYNNE

1986

[Reyna Meinert] appears to be following the example of her mother, who, interestingly, epitomizes (along with Hanna Roth, a dwarf psychic and maker of women's hats) both Vienna and National Socialism. Her mother is a beauty of boundless charm; there is a picture of Hitler kissing her hand and a rumor that he summoned her to his bed. The American soldiers who are supposedly intent on the great work of denazification are enchanted by her and intrigued by Hanna Roth, whom they provide with teeth and who becomes a storyteller and the idol of children. (Am I, by the way, alone in the view that psychic dwarfs are slightly overrepresented in contemporary letters?) In any case, the rather staid and decorous narrative foreground of the novel, the true-to-type conclusion that accounts for the title, exists in an interesting tension with a background of grand-scale desolation. In the quite banal serenity of the Meinert family, Vienna preserves itself. How can the city be denazified if, as Reyna says, it was not Hitler who raped Vienna, but Vienna who raped Hitler? She imagines him in the days of his poverty strolling the streets, hungry, dazzled, excluded. ''Vienna will haunt young strangers, taunt them. No one could escape our heritage, the invincible ardor of generations who had worked to make life prettier.'' The imperial city, with its bodacious claims on one's admiration, the officialized erotica of its monuments, the neo-venerable style of its architecture, gave Hitler his no-tions of civilization. The Russians and Americans who occupy the city are ravished in their turn. Denazification becomes a matter of shaving mustaches and allowing ''Hitler-blond'' hair to grow in, discovering Jewish ancestors and extenuating motives and finding ways to be useful to the Americans. This is not to say that she glosses over the devastating aspects of the period. ''Vienna was the city of love, of music, of flowers, and the devastation there was a sharp contrast,'' she said. ''The terrible things in my book are even more terrible because there is more sweetness; the central character is so lovable, it makes the hurt worse.'' The author said the story of a young girl seeking love amid horrible surroundings is relevant, because today's society has ''a multiplicity of deceit.'' She added that reports of former United Nations Secretary General Kurt Waldheim's service in the German Army give the novel another, unexpected relevance, because the book deals with the effort to ''remember to forget'' dreadful aspects of one's past, an effort that Mr. Waldheim has been accused of.

Book Review