Catalogue Search | MBRL

Search Results Heading

Explore the vast range of titles available.

MBRLSearchResults

-

DisciplineDiscipline

-

Is Peer ReviewedIs Peer Reviewed

-

Item TypeItem Type

-

Is Full-Text AvailableIs Full-Text Available

-

YearFrom:-To:

-

More FiltersMore FiltersSubjectPublisherSourceLanguagePlace of PublicationContributors

Done

Filters

Reset

2

result(s) for

"Bombings France Paris History 19th century"

Sort by:

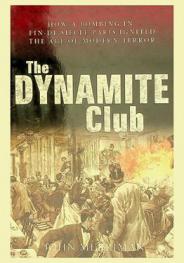

The dynamite club : how a bombing in fin-de-siecle Paris ignited the age of modern terror

On a February evening in 1894, a young radical intellectual named Emile Henry drank two beers at an upscale Parisian restaurant, then left behind a bomb as a parting gift. This incident, which rocked the French capital, lies at the heart of this account of Henry and his cohorts and the war they waged against the bourgeoisie.

How to Make an Anarchist-Terrorist: An Essay on the Political Imaginary in Fin-De-Siècle France

2010

This essay centers on the debate that surrounded the anarchist-terrorists of France in the 1890s. As a wave of bombings washed over Paris, commentators argued over the source of terrorism. With an eye toward a handful of notorious French anarchists—Ravachol, Auguste Vaillant, Emile Henry—they asked: How do you make an anarchist-terrorist? The debate that followed offers a window on the political imaginary of the French Third Republic in the years before the Dreyfus Affair. At times, the response to the anarchist bombings took the shape of a proxy war over the issues that moved French politics in the 1890s. But it was more than just this. For all of its variety, the debate centered on the problem of intellectual responsibility and gave form to the specter of the dangerous, rootless intellectual. There is a larger lesson in this tale, for the debate over the anarchistterrorists of fin-de-siècle France makes for a revealing case study in the ways in which democratic societies respond to the threat of homegrown terrorism. It demonstrates the difficult challenge that terrorism poses to democratic societies and shows just how easily political-cultural interests can hijack discussions of terrorism.

Journal Article