Catalogue Search | MBRL

Search Results Heading

Explore the vast range of titles available.

MBRLSearchResults

-

DisciplineDiscipline

-

Is Peer ReviewedIs Peer Reviewed

-

Series TitleSeries Title

-

Reading LevelReading Level

-

YearFrom:-To:

-

More FiltersMore FiltersContent TypeItem TypeIs Full-Text AvailableSubjectCountry Of PublicationPublisherSourceTarget AudienceDonorLanguagePlace of PublicationContributorsLocation

Done

Filters

Reset

6,328

result(s) for

"First language"

Sort by:

Look out, kindergarten, here I come! = ئPrepâarate, kindergarten! ئallâa voy! /cby = por Nancy Carlson ; translated by Teresa Mlawer

by

Carlson, Nancy L

,

Mlawer, Teresa

in

Kindergarten Juvenile fiction.

,

First day of school Juvenile fiction.

,

Kindergarten Fiction.

2004

Even though Henry is looking forward to going to kindergarten, he is not sure about staying once he first gets there.

Does Language Matter? Identity-First Versus Person-First Language Use in Autism Research: A Response to Vivanti

by

Hanlon, Jacqueline

,

Williams, Gemma Louise

,

Botha, Monique

in

Aggression

,

Autism

,

Autism Spectrum Disorders

2023

In response to Vivanti’s ‘Ask The Editor…’ paper [Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 691–693], we argue that the use of language in autism research has material consequences for autistic people including stigmatisation, dehumanisation, and violence. Further, that the debate in the use of person-first language versus identity-first language should centre first and foremost on the needs, autonomy, and rights of autistic people, so in to preserve their rights to self-determination. Lastly, we provide directions for future research.

Journal Article

Quâe nervios! : el primer dâia de sic escuela

by

Danneberg, Julie, 1958-

,

Love, Judith DuFour, ill

,

Mlawer, Teresa

in

First day of school Fiction.

,

Schools Fiction.

,

Teachers Fiction.

2006

Sarah is afraid to start at a new school, but both she and the reader are in for a surprise when she gets to her class.

Language acquisition in the digital age

2021

This article reviews prominent research on non-English-speaking children’s extramural acquisition of English through digital media, and examines the understudied scenario of possible effects of such second language (L2) English input on domestically dominant but globally small first languages (L1s), with Icelandic as the test case. We outline the main results of the children’s part of the Modeling the Linguistic Consequences of Digital Language Contact (MoLiCoDiLaCo) research project, which targeted 724 3–12-year-old Icelandic-speaking children. The focus is on English input and its relationship to the children’s Icelandic/English vocabulary and Icelandic grammar. Although a causal relationship between digital English and reduced/incompletely acquired Icelandic is often assumed in public discourse, our results do not show large-scale effects of L2 digital English on L1 Icelandic. English still seems to be a relatively small part of Icelandic children’s language environment, and although we find some indications of contact induced/reinforced language change, i.e. in the standard use of the subjunctive, as well as reduced MLU/NDW (mean length of utterance/number of different words) in the Icelandic language samples, we do not find pervasive effects of L2 English on L1 Icelandic. On the other hand, the results show contextual L2 learning of English by Icelandic-speaking children through mostly receptive digital input. Thus, the results imply that English digital language input contributes mainly to L2 English skills without adversely affecting L1 Icelandic.

Journal Article

Language Preferences in the Dutch Autism Community: A Social Psychological Approach

2024

This research examined the preference for identity-first language (IFL) versus person-first language (PFL) among 215 respondents (

M

age

= 30.24 years,

SD

= 9.92) from the Dutch autism community. We found that a stronger identification with the autism community and a later age of diagnosis predicted a stronger IFL preference and a weaker PFL preference. Both effects were mediated by the perceived consequences (justice to identity, prejudice reduction) of PFL. Participants’ own explanations were in line with these statistical analyses but also provided nuance to the IFL-PFL debate. Our results are consistent with the Social Identity Approach (Reicher et al.,

2010

) and Identity Uncertainty Theory (Hogg,

2007

) and demonstrate the value of a social psychological approach to study disability language preferences.

Journal Article

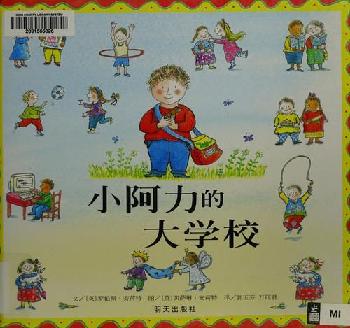

Xiaoali de da xue xiao

by

Anholt, Laurence author

,

Anholt, Laurence. Billy and the big new school

,

Anholt, Catherine Illustrator

in

Chinese language Texts

,

First day of school Juvenile fiction

,

Children's stories, English Translations into Chinese

2012

Billy is nervous about starting school, but as he cares for a sparrow that eventually learns to fly on its own, he realizes that he too can look after himself.

Mapping the unconscious maintenance of a lost first language

by

Pierce, Lara J.

,

Genesee, Fred

,

Delcenserie, Audrey

in

Acoustic Stimulation - methods

,

acoustics

,

Adolescent

2014

Significance Using functional MRI we examined the unconscious influence of early experience on later brain outcomes. Internationally adopted (IA) children (aged 9–17 years), who were completely separated from their birth language (Chinese) at 12.8 mo of age, on average, displayed brain activation to Chinese linguistic elements that precisely matched that of native Chinese speakers, despite the fact that IA children had no subsequent exposure to Chinese and no conscious recollection of that language. Importantly, activation differed from monolingual French speakers with no Chinese exposure, despite all participants hearing identical acoustic stimuli. The similarity between adoptees and Chinese speakers clearly illustrates that early acquired information is maintained in the brain and that early experiences unconsciously influence neural processing for years, if not indefinitely.

Optimal periods during early development facilitate the formation of perceptual representations, laying the framework for future learning. A crucial question is whether such early representations are maintained in the brain over time without continued input. Using functional MRI, we show that internationally adopted (IA) children from China, exposed exclusively to French since adoption (mean age of adoption, 12.8 mo), maintained neural representations of their birth language despite functionally losing that language and having no conscious recollection of it. Their neural patterns during a Chinese lexical tone discrimination task matched those observed in Chinese/French bilinguals who have had continual exposure to Chinese since birth and differed from monolingual French speakers who had never been exposed to Chinese. They processed lexical tone as linguistically relevant, despite having no Chinese exposure for 12.6 y, on average, and no conscious recollection of that language. More specifically, IA participants recruited left superior temporal gyrus/planum temporale, matching the pattern observed in Chinese/French bilinguals. In contrast, French speakers who had never been exposed to Chinese did not recruit this region and instead activated right superior temporal gyrus. We show that neural representations are not overwritten and suggest a special status for language input obtained during the first year of development.

Journal Article

Problems of Learners with L1 Background (Non-Latin Mother Tongue) Learning Indonesian as L2

by

Andajani, Kusubakti

,

Suyitno, Imam

,

Rahmawati, Ida Yeni

in

differentiated learning strategies

,

first language interference (l1 (non-latin mother language)

,

indonesian for foreign speakers (bipa)

2025

Background/purpose. Indonesian uses Latin script, so students whose first language background (L1) is a non-Latin language will experience difficulties in understanding it. The purpose of this study is to explore the similarities and differences in the problems faced by Indonesian students (L2) with a non-Latin background (L1) and students with a Latin background (L1). Materials / Methods. The research design used is qualitative and exploratory. Data were collected through observation and interviews to find initial data, which was then continued with a literature study to compare the findings of problems faced by non-Latin L1 (non-Latin mother tongue) students with Latin students in learning Indonesian (L2). Results. The results of the study show that Indonesian as a second language (L2) students with a non-Latin first language (L1) background, especially Mandarin speakers, experience various difficulties both from linguistic and non-linguistic aspects. From the linguistic side, the main challenges include mispronunciation of certain letters, use of punctuation, writing Latin letters, and understanding the morphological structure of the Indonesian language. From the non-linguistic side, problems were found, such as low learning motivation, limited learning time, lack of social interaction in Indonesian, and difficulty in adjusting to Indonesian norms and culture. Conclusion. Differences in first language background (Latin vs. non-Latin) significantly affect the type and level of difficulty in learning Indonesian. Therefore, strategies for teaching Indonesian as a foreign language need to be specifically adjusted to the characteristics and needs of each group of students to optimize learning outcomes.

Journal Article